More about machine learning: Machine Learning with Python

- Linear regression

- Multiple linear regression

- Ridge, Lasso, Elastic Net

- Logistic regression

- Decision trees

- Random forest

- Gradient boosting

- Machine learning with Python and Scikitlearn

- Neural Networks

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

- Clustering with python

- Anomaly detection with PCA

- Face Detection and Recognition

- Introduction to Graphs and Networks

Introduction¶

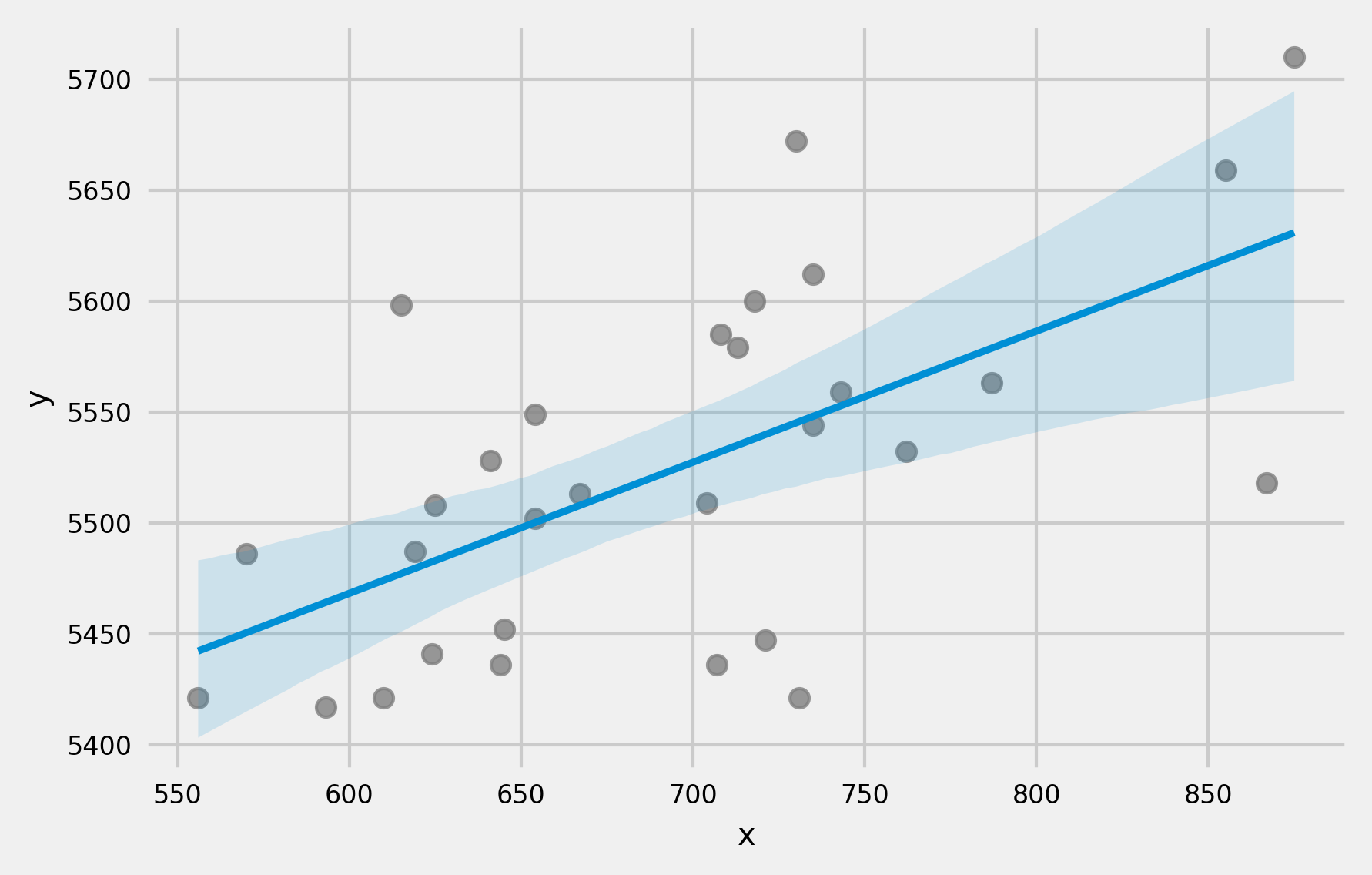

Multiple linear regression is a statistical method that attempts to model the relationship between a continuous variable and two or more independent variables by fitting a linear equation. Multiple linear regression allows generating a model in which the value of the dependent or response variable ($Y$) is determined from a set of independent variables called predictors ($X_1$, $X_2$, $X_3$…). It is an extension of simple linear regression, so it is essential to understand the latter.

Multiple regression models can be used to predict the value of the dependent variable or to evaluate the influence that predictors have on it (the latter should be analyzed with caution to avoid misinterpreting cause-effect relationships).

Throughout this document, the theoretical foundations of multiple linear regression, the main practical aspects to consider, and examples of how to create this type of model in Python are progressively described.

Linear Regression Models in Python

Two of the most widely used implementations of linear regression models in Python are: scikit-learn and statsmodels. Although both are highly optimized, Scikit-learn is primarily oriented towards prediction, so it has very few functionalities that display the many model characteristics that need to be analyzed for inference. Statsmodels is much more comprehensive in this regard.

✏️ Note

Multiple linear regression is an extension of simple linear regression, so it is recommended to first read Linear Regression with Python.

Mathematical Definition¶

The linear regression model (Legendre, Gauss, Galton, and Pearson) considers that, given a set of observations $\{y_i, x_{i1}, ..., x_{ip}\}^{n}_{i=1}$, the mean $\mu_y$ of the response variable $y$ is linearly related to the regressor variable(s) $x_1$ ... $x_p$ according to the equation:

$$\mu_y = \beta_0 + \beta_1 x_{1} + \beta_2 x_{2} + ... + \beta_p x_{p}$$The result of this equation is known as the population regression line, and captures the relationship between the predictors and the mean of the response variable.

Another definition frequently found in statistics books is:

$$y_i= \beta_0 + \beta_1 x_{i1} + \beta_2 x_{i2} + ... + \beta_p x_{ip} +\epsilon_i$$In this case, reference is being made to the value of $y$ for a specific observation $i$. The value of a particular observation will never be exactly equal to the average, hence the error term $\epsilon$ is added.

In both cases, the interpretation of the model elements is the same:

$\beta_{0}$: is the intercept, corresponding to the average value of the response variable $y$ when all predictors are zero.

$\beta_{j}$: the partial regression coefficients of each predictor indicate the expected average change in the response variable $y$ when increasing the predictor variable $x_{j}$ by one unit, while keeping the other variables constant.

Computationally, these calculations are more efficient if performed in matrix form:

$$\mathbf{y}=\mathbf{X} \mathbf{\beta}+\epsilon$$$$\mathbf{y}=\begin{bmatrix} y_1\\ y_2\\ ...\\ y_n\end{bmatrix} \ , \ \ \ \mathbf{X}=\begin{bmatrix} 1 & x_{11} & ... & x_{1p}\\ 1 & x_{21} & ... & x_{2p}\\ 1 & ... & ... & ... \\ 1 & x_{n1} & ... &x_{np}\\ \end{bmatrix} \ , \ \ \ \mathbf{\beta}=\begin{bmatrix} \beta_0\\ \beta_1\\ ...\\ \beta_p\end{bmatrix} \ , \ \ \ \mathbf{\epsilon}=\begin{bmatrix} \epsilon_1\\ \epsilon_2\\ ...\\ \epsilon_n\end{bmatrix}$$The coefficient estimates are obtained by minimizing the sum of squared residuals:

$$\hat{\boldsymbol{\beta}} = \underset{\boldsymbol{\beta}}{\arg\min} (\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{X} \boldsymbol{\beta})^T(\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{X} \boldsymbol{\beta})$$The solution to this optimization problem (under the assumption that $\mathbf{X}^T\mathbf{X}$ is invertible) is:

$$\hat{\boldsymbol{\beta}} = (\mathbf{X}^T\mathbf{X})^{-1}\mathbf{X}^T\mathbf{y}$$Once the coefficients are estimated, the estimates for each observation ($\hat{y}_i$) can be obtained:

$$\hat{y}_i= \hat{\beta}_0 + \hat{\beta}_1 x_{i1} + \hat{\beta}_2 x_{i2} + ... + \hat{\beta}_p x_{ip}$$Finally, the estimate of the model variance ($\hat{\sigma}^2$) is obtained as:

$$\hat{\sigma}^2 = \frac{\sum^n_{i=1} \hat{\epsilon}_i^2}{n-p-1} = \frac{\sum^n_{i=1} (y_i - \hat{y}_i)^2}{n-p-1}$$where $n$ is the number of observations and $p$ is the number of predictors.

Model Interpretation¶

The main elements to interpret in a linear regression model are the predictor coefficients:

$\beta_{0}$ is the intercept, corresponding to the expected value of the response variable $y$ when all predictors are zero.

$\beta_{j}$ the partial regression coefficients of each predictor indicate the expected average change in the response variable $y$ when increasing the predictor variable $x_{j}$ by one unit, while keeping the other variables constant.

The magnitude of each partial regression coefficient depends on the units in which the corresponding predictor variable is measured, so its magnitude is not associated with the importance of each predictor.

To compare the impact that each variable has on the model, standardized partial coefficients are used, which are obtained by standardizing (subtracting the mean and dividing by the standard deviation) the predictor variables prior to fitting the model. In this case, $\beta_{0}$ corresponds to the expected value of the response variable when all predictors are at their average value, and $\beta_{j}$ is the expected average change in the response variable when increasing the predictor variable $x_{j}$ by one standard deviation, while keeping the other variables constant.

While regression coefficients are usually the first objective when interpreting a linear model, there are many other aspects (significance of the model as a whole, significance of predictors, normality condition...). The latter are usually treated with little detail when the sole objective of the model is to make predictions, however, they are very relevant if one wants to perform inference, that is, to explain the relationships between the predictors and the response variable. Throughout this document, each of them will be introduced.

Meaning of "linear"

The term "linear" in regression models refers to the fact that parameters are incorporated into the equation in a linear fashion, not that the relationship between each predictor and the response variable necessarily follows a linear pattern.

The following equation shows a linear model in which predictor $x_1$ is not linear with respect to y:

$$y = \beta_0 + \beta_1x_1 + \beta_2log(x_1) + \epsilon$$In contrast, the following is not a linear model:

$$y = \beta_0 + \beta_1x_1^{\beta_2} + \epsilon$$Sometimes, some nonlinear relationships can be transformed so that they can be expressed linearly. For example, a multiplicative model with multiplicative error:

$$y = \beta_0 x_1^{\beta_1} \epsilon$$can be linearized by taking logarithms:

$$\log(y)=\log(\beta_0) + \beta_1\log(x_1) + \log(\epsilon)$$Model Goodness of Fit¶

Once the model is fitted, it is necessary to verify its usefulness since, even though it is the line that best fits the observations among all possible ones, it may have a large error. The most commonly used metrics to measure fit quality are: the residual standard error and the coefficient of determination $R^2$.

Residual Standard Error (RSE)

Measures the average deviation of any point estimated by the model from the regression line. It has the same units as the response variable. One way to determine if the RSE value is high is to divide it by the average value of the response variable, thus obtaining a % of the deviation.

$$RSE = \sqrt{\frac{1}{n-p-1}RSS}$$In simple linear models, since there is a single predictor, $(n-p-1) = (n-2)$.

Coefficient of Determination $R^2$

$R^2$ describes the proportion of variance in the response variable explained by the model and relative to the total variance. Its value is bounded between 0 and 1. Being dimensionless, it has the advantage over RSE of being easier to interpret.

$$R^{2}=\frac{\text{Total sum of squares - Residual sum of squares}}{\text{Total sum of squares}}=$$$$1-\frac{\text{Residual sum of squares}}{\text{Total sum of squares}} = $$$$1-\frac{\sum(y_i - \hat{y}_i)^2}{\sum(y_i-\overline{y})^2}$$In multiple linear models, the more predictors included in the model, the higher the value of $R^2$. This is because, no matter how little, each predictor will explain part of the variability observed in $y$. This is why $R^2$ cannot be used to compare models with different numbers of predictors.

$R^2_{adjusted}$ introduces a penalty to the value of $R^2$ for each predictor added to the model. The value of the penalty depends on the number of predictors used and the sample size, that is, on the degrees of freedom. The larger the sample size, the more predictors can be incorporated into the model. $R^2_{adjusted}$ allows finding the best model, the one that best explains the variability of $y$ with the fewest number of predictors.

$$R^{2}_{adjusted} = 1 - \frac{RSS}{TSS} \times \frac{n-1}{n-p-1} = 1 - (1-R^{2}) \times \frac{n-1}{n-p-1} = 1-\frac{RSS/df_{e}}{TSS/df_{t}}$$where $RSS$ is the residual sum of squares (Sum of Squares Residual), $TSS$ is the total sum of squares (Total Sum of Squares), $n$ is the sample size, $p$ is the number of predictors introduced into the model, $df_e = n-p-1$ are the error degrees of freedom, and $df_t = n-1$ are the total degrees of freedom.

Model Significance F-test¶

One of the first results to evaluate when fitting a model is the result of the $F$ significance test. This test answers the question of whether the model as a whole is capable of predicting the response variable better than would be expected by chance, or equivalently, whether at least one of the predictors that form the model contributes significantly. To perform this test, the sum of squared residuals of the model of interest is compared with that of the model without predictors, formed only by the mean (also known as total sum of squares, $TSS$).

$$F = \frac{(TSS - RSS)/p}{RSS/(n-p-1)}$$Frequently, the null and alternative hypotheses of this test are described as:

$H_0$: $\beta_1 = \beta_2 = ... = \beta_p = 0$

$H_a$: at least one $\beta_j \neq 0$

If the $F$ test is significant, it implies that the model is useful, but not that it is the best. It could be that some of its predictors are not necessary.

Predictor Significance¶

In most cases, although the regression study is applied to a sample, the ultimate goal is to obtain a linear model that explains the relationship between variables in the entire population. This means that the generated model is an estimate of the population relationship based on the relationship observed in the sample and, therefore, is subject to variations. For each of the coefficients of the linear regression equation ($\beta_j$), its significance (p-value) and confidence interval can be calculated. The most commonly used statistical test is the t-test (there are non-parametric alternatives).

The significance test for the coefficients ($\beta_j$) of the linear model considers as hypotheses:

$H_0$: predictor $x_j$ does not contribute to the model ($\beta_j = 0$), in the presence of the other predictors.

$H_a$: predictor $x_j$ does contribute to the model ($\beta_j \neq 0$), in the presence of the other predictors. In the case of simple linear regression, it can also be interpreted as there being a linear relationship between both variables so the model slope is different from zero $\beta_j \neq 0$.

Calculation of the T statistic and p-value:

$$t = \frac{\hat{\beta}_j}{SE(\hat{\beta}_j)}$$where $SE(\hat{\beta}_j)$ is the standard error of the coefficient $\hat{\beta}_j$. In multiple linear regression, the standard error depends on all predictors and their correlations. In matrix notation:

$$Var(\hat{\boldsymbol{\beta}}) = \sigma^2 (\mathbf{X}^T\mathbf{X})^{-1}$$where $SE(\hat{\beta}_j) = \sqrt{Var(\hat{\beta}_j)}$.

The error variance $\sigma^2$ is estimated from the Residual Standard Error (RSE), which can be understood as the average difference that the response variable deviates from the true regression line. In the case of simple linear regression, RSE is equivalent to:

$$RSE = \sqrt{\frac{1}{n-2}RSS} = \sqrt{\frac{1}{n-2}\sum^n_{i=1}(y_i -\hat{y}_i)^2}$$For multiple linear regression:

$$RSE = \sqrt{\frac{1}{n-p-1}RSS} = \sqrt{\frac{1}{n-p-1}\sum^n_{i=1}(y_i -\hat{y}_i)^2}$$Degrees of freedom (df) = $n - p - 1$ where $n$ is the number of observations and $p$ is the number of predictors

p-value = P(|t| > calculated value of t)

Confidence Intervals

$$\hat{\beta}_j \pm t_{df}^{\alpha/2} SE(\hat{\beta}_j)$$The smaller the number of observations $n$, the lower the ability to calculate the standard error of the model. As a consequence, the accuracy of the estimated regression coefficients is reduced. This is particularly important in multiple regression.

In models generated with statsmodels, the value of the regression coefficients is returned along with the value of the $t$ statistic obtained for each one, the p-values and the corresponding confidence intervals. This allows knowing, in addition to the estimates, whether they are significantly different from 0, that is, whether they contribute to the model.

For the calculations described above to be valid, it must be assumed that the residuals are independent and normally distributed with mean 0 and variance $\sigma^2$. When the normality condition is not satisfied, there is the possibility of resorting to permutation tests to calculate significance (p-value) and to bootstrapping to calculate confidence intervals.

Categorical Variables as Predictors¶

When a categorical variable is introduced as a predictor, one level is considered the reference level (usually coded as 0) and the rest of the levels are compared to it. In the case that the categorical predictor has more than two levels, what are known as dummy variables or one-hot-encoding are generated, which are variables created for each of the levels of the categorical predictor and can take the value 0 or 1. Each time the model is used to predict a value, only one dummy variable per predictor acquires the value 1 (the one that matches the value the predictor takes in that case) while the rest are considered 0. The value of the partial regression coefficient $\beta_j$ of each dummy variable indicates the average percentage by which that level influences the dependent variable $y$ compared to the reference level of that predictor.

The idea of dummy variables is better understood with an example. Suppose a model in which the response variable weight is predicted based on the height and nationality of the subject. The nationality variable is qualitative with 3 levels (American, European, and Asian). Despite the initial predictor being nationality, a new variable is created for each level, whose value can be 0 or 1. Such that the complete model equation is:

$$weight = \beta_0 + \beta_1height + \beta_2American + \beta_3European + \beta_4Asian$$If the subject is European, the dummy variables American and Asian are considered 0, so the model for this case becomes:

$$weight = \beta_0 + \beta_1height + \beta_3European$$Prediction¶

Once a valid model has been generated, it is possible to predict the value of the response variable $y$ for new values of the predictor variables $x$. It is important to note that predictions should, a priori, be limited to the range of values within which the observations used to train the model are found. This is important since, although linear models can be extrapolated, only in this region is there certainty that the conditions for the model to be valid are met. To calculate the predictions, the equation generated by regression is used.

$$\hat{y}_i= \hat{\beta}_0 + \hat{\beta}_1 x_{i1} + \hat{\beta}_2 x_{i2} + ... + \hat{\beta}_p x_{ip}$$Since the model has been obtained from a sample, the estimates of the regression coefficients have an associated error and, therefore, so do the values of the predictions generated with them. There are two ways to measure the uncertainty associated with a prediction:

- Confidence intervals: interval of the average expected value of the response variable $y$ for a given set of predictor values $\mathbf{x}_0$.

- Prediction intervals: interval for a new individual observation of the response variable $y$ for a given set of predictor values $\mathbf{x}_0$.

where $\mathbf{x}_0 = [1, x_{01}, x_{02}, ..., x_{0p}]^T$ is the vector of predictor values (including the intercept term as 1) for which we want to make a prediction, and $MSE = \hat{\sigma}^2 = \frac{RSS}{n-p-1}$ is the mean squared error of the model.

While both seem similar, the difference lies in the fact that confidence intervals apply to the average value expected of $y$ for a given set of predictor values, while prediction intervals apply to new individual observations. For this reason, prediction intervals are always wider than confidence intervals (note the additional "1" term in the prediction interval formula, which accounts for the variability of individual observations around the mean).

A characteristic that derives from the way the margin of error is calculated in confidence and prediction intervals is that the interval widens as the predictor values move away from the center of the observed data (where the model was fitted).

Why does this occur? The term $\mathbf{x}_0^T(\mathbf{X}^T\mathbf{X})^{-1}\mathbf{x}_0$ in the formulas quantifies how far the new observation $\mathbf{x}_0$ is from the center of the training data in the predictor space. The farther the new observation is from the center of the data used to train the model, the larger this term becomes and, consequently, the wider the confidence and prediction intervals.

Model Validation¶

Once the best model that can be created with the available data has been selected, its ability to predict new observations that have not been used to train it must be tested, thus verifying whether the model can be generalized. A commonly used strategy is to randomly divide the data into two groups, fit the model with the first group, and estimate the accuracy of the predictions with the second.

The appropriate size of the partitions depends largely on the amount of data available and the certainty needed in the error estimate, 80%-20% usually gives good results.

Conditions for Multiple Linear Regression¶

For a least squares linear regression model, and the conclusions derived from it, to be completely valid, the assumptions on which its mathematical development is based must be verified. In practice, they are rarely all met, or it can be demonstrated that they are all met, however, this does not mean that the model is not useful. The important thing is to be aware of them and the impact this has on the conclusions drawn from the model.

No collinearity or multicollinearity:

In multiple linear models, predictors must be independent, there should be no collinearity between them. Collinearity occurs when a predictor is linearly related to one or more of the other predictors in the model. As a consequence of collinearity, the individual effect that each predictor has on the response variable cannot be accurately identified, which translates into an increase in the variance of the estimated regression coefficients to the point that it becomes impossible to establish their statistical significance. Moreover, small changes in the data cause large changes in the coefficient estimates. Although collinearity proper exists only if the simple or multiple correlation coefficient between predictors is 1, which rarely occurs in reality, the so-called near-collinearity or imperfect multicollinearity is frequently encountered.

There is no specific statistical method to determine the existence of collinearity or multicollinearity among the predictors of a regression model, however, numerous practical rules have been developed that try to determine to what extent they affect the model. The recommended steps to follow are:

If the coefficient of determination $R^2$ is high but none of the predictors is significant, there are indications of collinearity.

Create a correlation matrix in which the linear relationship between each pair of predictors is calculated. It is important to note that, despite not obtaining any high correlation coefficient, multicollinearity is not guaranteed to be absent. It may be the case that there is an almost perfect linear relationship between three or more variables and the simple correlations between pairs of these same variables are not greater than 0.5.

Generate a simple linear regression model between each of the predictors versus the rest. If in any of the models the *coefficient of determination $R^2$ is high, it would be signaling a possible collinearity.

Tolerance (TOL) and Variance Inflation Factor (VIF). These are two parameters that quantify the same thing (one is the inverse of the other). The VIF of each predictor is calculated according to the following formula:

Where $R_j^2$ is obtained from the regression of predictor $X_j$ on the other predictors. This is the most recommended option, the reference limits usually used are:

VIF = 1: total absence of collinearity

1 < VIF < 5: regression may be affected by some collinearity.

5 < VIF < 10: regression may be highly affected by some collinearity.

The tolerance term is $\frac{1}{VIF}$ so the recommended limits are between 1 and 0.1.

If collinearity is found between predictors, there are two possible solutions. The first is to exclude one of the problematic predictors, trying to keep the one that, in the researcher's judgment, is really influencing the response variable. This measure usually does not have much impact on the model in terms of its predictive capacity since, due to collinearity, the information provided by one of the predictors is redundant in the presence of the other. The second option is to combine the collinear variables into a single predictor, although with the risk of losing its interpretation.

When trying to establish cause-effect relationships, collinearity can lead to very erroneous conclusions, making one believe that a variable is the cause when, in reality, it is another that is influencing that predictor.

Linear relationship between numerical predictors and the response variable

Each numerical predictor must be linearly related to the response variable $y$ while the other predictors are kept constant, otherwise they should not be introduced into the model. The most recommended way to check this is by plotting the model residuals against each of the predictors. If the relationship is linear, the residuals are distributed randomly around zero. These analyses are only approximate, since there is no way to know if the relationship is really linear when the rest of the predictors are kept constant.

Normal distribution of residuals

Residuals must be normally distributed with mean zero. To check this, histograms, normal quantile plots, or normality hypothesis tests are used.

Constant variance of the response variable (homoscedasticity)

The variance of the response variable must be constant across the entire range of predictors. To check this, the model residuals are usually plotted against each predictor. If the variance is constant, they are distributed randomly maintaining the same dispersion and without any specific pattern. A conical distribution is a clear identifier of lack of homoscedasticity. Homoscedasticity tests such as the Breusch-Pagan test can also be used.

The reason for this condition lies in the following: linear models assume that the response variable $y$ follows a normal distribution, whose mean $\mu$ can be modeled as a function of other variables (predictors) and whose variance $\sigma$ is calculated using a dispersion constant and a function $\nu(\mu)$. The latter means that the variance is not directly modeled as a function of the predictor variables but indirectly through its relationship with the mean and is a single value.

$$\hat{\sigma}^2 = \frac{\sum^n_{i=1} \hat{\epsilon}_i^2}{n-p-1} = \frac{\sum^n_{i=1} (y_i - \hat{y}_i)^2}{n-p-1}$$What impact can this have in practice? While the mean estimates obtained by these models are good, the associated uncertainties are not as good and, consequently, neither are the confidence and prediction intervals that can be calculated.

No autocorrelation (Independence)

The values of each observation are independent of the others. This is especially important to check when working with temporal measurements. It is recommended to plot the residuals ordered according to the time of recording of the observations, if there is a certain pattern there are indications of autocorrelation. The Durbin-Watson hypothesis test can also be used.

Outliers, high leverage or influential values

It is important to identify observations that are outliers or that may be influencing the model. The easiest way to detect them is through the residuals (see more details below).

Sample size

It is not a condition per se, but if there are not enough observations, predictors that are not really influential could appear to be so. A frequent recommendation is that the number of observations be at least between 10 and 20 times the number of predictors in the model.

Parsimony

This term refers to the fact that the best model is the one capable of explaining with greater precision the variability observed in the response variable using the fewest number of predictors, therefore, with fewer assumptions.

The vast majority of conditions are verified using residuals, therefore, the model is usually generated first and then the conditions are validated. In fact, fitting a model should be seen as an iterative process in which the model is fitted, its residuals are evaluated, and it is improved. This continues until an optimal model is reached.

Predictor Selection¶

When selecting the predictors that should be part of the model, several methods can be followed:

Hierarchical method: based on the analyst's criterion, certain predictors are introduced in a certain order.

Forced entry method: all predictors are introduced simultaneously.

Stepwise method: uses mathematical criteria to decide which predictors contribute significantly to the model and in what order they are introduced. Within this method, three strategies are distinguished:

Forward direction: The initial model does not contain any predictor, only the parameter $\beta_0$. From this, all possible models are generated by introducing a single variable from those available. The variable that improves the model the most is selected. Next, an attempt is made to increase the model by testing the introduction of the remaining variables one by one. If introducing any of them improves, it is also selected. In case several do, the one that increases the model's capacity the most is selected. This process is repeated until the point is reached where none of the variables left to incorporate improve the model.

Backward direction: The model starts with all available variables included as predictors. An attempt is made to eliminate each variable one by one, if the model improves, it is excluded. This method allows evaluating each variable in the presence of the others.

Double or mixed: It is a combination of forward and backward selection. It starts the same as forward but after each new incorporation, a test for extracting non-useful predictors is performed as in backward. It has the advantage that, as predictors are added, if any of those already present ceases to contribute to the model, it is eliminated.

The stepwise method requires some mathematical criterion to determine whether the model improves or worsens with each incorporation or extraction. There are several parameters used, among which $C_p$, $AIC$, $BIC$ and $R^2_{\text{adjusted}}$ stand out, each with advantages and disadvantages. The Akaike (AIC) method tends to be more restrictive and introduce fewer predictors than adjusted $R^2$. For the same data set, not all methods have to conclude with the same model.

It is common to find examples where predictor selection is based on the p-value associated with each one. While this method is simple and intuitive, it presents multiple problems: inflation of type I error due to multiple comparisons, elimination of the least significant predictors tends to increase the significance of the other predictors. For this reason, except for very simple cases with few predictors, it is preferable not to use p-values as a selection criterion.

In the case of categorical variables, if at least one of their levels is significant, the variable is considered to be so. It is worth mentioning that, if a variable is excluded from the model as a predictor, it means that it does not provide additional information to the model, but it may be related to the response variable.

Outliers¶

Regardless of whether the model has been accepted, it is always advisable to identify if there is any possible outlier, observation with high leverage or influential, since it could be conditioning the model to a large extent. The elimination of this type of observations should be analyzed in detail and depending on the purpose of the model. If the goal is predictive, a model without outliers or highly influential observations is usually able to predict most cases better. However, it is very important to pay attention to these values since, if they are not measurement errors, they may be the most interesting cases. The appropriate way to proceed when a possible outlier or influential value is suspected is to calculate the regression model including and excluding that value.

Example¶

A study wants to generate a model that allows predicting the average life expectancy of the inhabitants of a city based on different variables. Information is available on the average life expectancy of the inhabitants of 50 cities, along with sociodemographic information for each of them. Specifically, the following is known: the number of inhabitants, illiteracy level, income, murders, number of college graduates, frost days, area, and population density.

Libraries¶

The libraries used in this document are:

# Libraries

# ==============================================================================

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import seaborn as sns

import statsmodels.api as sm

import statsmodels.formula.api as smf

from statsmodels.stats.diagnostic import het_breuschpagan

from statsmodels.stats.outliers_influence import variance_inflation_factor

from statsmodels.tools.eval_measures import rmse

from scipy import stats

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from sklearn.feature_selection import SequentialFeatureSelector

from sklearn.linear_model import LinearRegression

Data¶

# Data download

# ==============================================================================

url = (

'https://raw.githubusercontent.com/JoaquinAmatRodrigo/'

'Estadistica-machine-learning-python/master/data/state_x77.csv'

)

data = pd.read_csv(url, sep=',')

# Rename columns

# ==============================================================================

names_dict = {

'habitantes': 'population',

'ingreso': 'income',

'analfabetismo': 'illiteracy',

'esp_vida': 'life_expectancy',

'asesinatos': 'murder',

'universitarios': 'college_graduate',

'heladas': 'frosts',

'area': 'area',

'densidad_pob': 'population_density'

}

data = data.rename(columns=names_dict)

display(data.info())

data.head(3)

<class 'pandas.core.frame.DataFrame'> RangeIndex: 50 entries, 0 to 49 Data columns (total 9 columns): # Column Non-Null Count Dtype --- ------ -------------- ----- 0 population 50 non-null int64 1 ingresos 50 non-null int64 2 illiteracy 50 non-null float64 3 life_expectancy 50 non-null float64 4 murder 50 non-null float64 5 college_graduate 50 non-null float64 6 frosts 50 non-null int64 7 area 50 non-null int64 8 densidad_pobl 50 non-null float64 dtypes: float64(5), int64(4) memory usage: 3.6 KB

None

| population | ingresos | illiteracy | life_expectancy | murder | college_graduate | frosts | area | densidad_pobl | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 3615 | 3624 | 2.1 | 69.05 | 15.1 | 41.3 | 20 | 50708 | 71.290526 |

| 1 | 365 | 6315 | 1.5 | 69.31 | 11.3 | 66.7 | 152 | 566432 | 0.644384 |

| 2 | 2212 | 4530 | 1.8 | 70.55 | 7.8 | 58.1 | 15 | 113417 | 19.503249 |

# Split data into train and test

# ==============================================================================

X = data.drop(columns='life_expectancy')

y = data['life_expectancy']

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(

X,

y.values.reshape(-1,1),

train_size = 0.8,

random_state = 1234,

shuffle = True

)

Relationship between variables¶

The first step when creating a multiple linear model is to study the relationship that exists between variables. This information is critical for identifying which may be the best predictors for the model, and for detecting collinearity between predictors. Additionally, it is advisable to analyze the distribution of each variable.

✏️ Note

For more detailed information on linear correlation and probability distributions visit:

# Linear correlation between numerical variables

# ==============================================================================

corr_matrix = data.corr(method='pearson')

tril = np.tril(np.ones(corr_matrix.shape)).astype(bool)

corr_matrix[tril] = np.nan

corr_matrix_tidy = corr_matrix.stack().reset_index(name='r')

corr_matrix_tidy = corr_matrix_tidy.rename(columns={'level_0': 'variable_1', 'level_1': 'variable_2'})

corr_matrix_tidy = corr_matrix_tidy.dropna()

corr_matrix_tidy['r_abs'] = corr_matrix_tidy['r'].abs()

corr_matrix_tidy = corr_matrix_tidy.sort_values('r_abs', ascending=False).reset_index(drop=True)

corr_matrix_tidy

| variable_1 | variable_2 | r | r_abs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | life_expectancy | murder | -0.780846 | 0.780846 |

| 1 | illiteracy | murder | 0.702975 | 0.702975 |

| 2 | illiteracy | frosts | -0.671947 | 0.671947 |

| 3 | illiteracy | college_graduate | -0.657189 | 0.657189 |

| 4 | ingresos | college_graduate | 0.619932 | 0.619932 |

| 5 | illiteracy | life_expectancy | -0.588478 | 0.588478 |

| 6 | life_expectancy | college_graduate | 0.582216 | 0.582216 |

| 7 | murder | frosts | -0.538883 | 0.538883 |

| 8 | murder | college_graduate | -0.487971 | 0.487971 |

| 9 | ingresos | illiteracy | -0.437075 | 0.437075 |

| 10 | college_graduate | frosts | 0.366780 | 0.366780 |

| 11 | ingresos | area | 0.363315 | 0.363315 |

| 12 | population | murder | 0.343643 | 0.343643 |

| 13 | area | densidad_pobl | -0.341389 | 0.341389 |

| 14 | ingresos | life_expectancy | 0.340255 | 0.340255 |

| 15 | college_graduate | area | 0.333542 | 0.333542 |

| 16 | population | frosts | -0.332152 | 0.332152 |

| 17 | ingresos | densidad_pobl | 0.329968 | 0.329968 |

| 18 | life_expectancy | frosts | 0.262068 | 0.262068 |

| 19 | population | densidad_pobl | 0.246228 | 0.246228 |

| 20 | ingresos | murder | -0.230078 | 0.230078 |

| 21 | murder | area | 0.228390 | 0.228390 |

| 22 | ingresos | frosts | 0.226282 | 0.226282 |

| 23 | population | ingresos | 0.208228 | 0.208228 |

| 24 | murder | densidad_pobl | -0.185035 | 0.185035 |

| 25 | population | illiteracy | 0.107622 | 0.107622 |

| 26 | life_expectancy | area | -0.107332 | 0.107332 |

| 27 | population | college_graduate | -0.098490 | 0.098490 |

| 28 | life_expectancy | densidad_pobl | 0.091062 | 0.091062 |

| 29 | college_graduate | densidad_pobl | -0.088367 | 0.088367 |

| 30 | illiteracy | area | 0.077261 | 0.077261 |

| 31 | population | life_expectancy | -0.068052 | 0.068052 |

| 32 | frosts | area | 0.059229 | 0.059229 |

| 33 | population | area | 0.022544 | 0.022544 |

| 34 | illiteracy | densidad_pobl | 0.009274 | 0.009274 |

| 35 | frosts | densidad_pobl | 0.002277 | 0.002277 |

# Correlation matrix heatmap

# ==============================================================================

fig, ax = plt.subplots(nrows=1, ncols=1, figsize=(4, 4))

sns.heatmap(

corr_matrix,

annot = True,

cbar = False,

annot_kws = {"size": 8},

vmin = -1,

vmax = 1,

center = 0,

cmap = "viridis",

square = True,

ax = ax

)

ax.set_xticklabels(

ax.get_xticklabels(),

rotation = 45,

horizontalalignment = 'right',

)

ax.tick_params(labelsize = 10)

# Distribution plot for each numerical variable

# ==============================================================================

# Adjust number of subplots based on number of columns

fig, axes = plt.subplots(nrows=3, ncols=3, figsize=(9, 6))

axes = axes.flat

numeric_columns = data.select_dtypes(include=np.number).columns

for i, colum in enumerate(numeric_columns):

sns.histplot(

data = data,

x = colum,

stat = "count",

kde = True,

color = (list(plt.rcParams['axes.prop_cycle'])*2)[i]["color"],

ax = axes[i]

)

axes[i].set_title(colum, fontsize = 10)

axes[i].tick_params(labelsize = 8)

axes[i].set_xlabel("")

fig.tight_layout()

plt.subplots_adjust(top = 0.9)

fig.suptitle('Distribution of numerical variables', fontsize = 12);

From the preliminary analysis, the following conclusions can be drawn:

The variables that have the strongest linear relationship with life expectancy are: murders (r= -0.78), illiteracy (r= -0.59), and college graduates (r= 0.58).

Murders and illiteracy are moderately correlated (r = 0.7), so it may be redundant to introduce both predictors into the model.

The variables population, area, and population density show an exponential distribution; a logarithmic transformation would likely make their distribution more normal.

Model Fitting¶

A first model is fitted using all available variables as predictors.

✏️ Note

Unlike the scikit-learn API, in the statsmodels library, the fit method returns a new object as a result instead of modifying the existing object.

# Fit model using formula mode (similar to R)

# ==============================================================================

# To fit the model using formula mode, the data must be

# stored in a single dataframe.

# train_data = X_train.assign(esp_vida = y_train).copy()

# model = smf.ols(

# formula = 'esp_vida ~ habitantes + ingresos + analfabetismo + asesinatos + universitarios + heladas + area + densidad_pobl',

# data = train_data

# )

# model_res = model.fit()

#print(model_res.summary())

# Fit model using X, y matrices (similar to scikit-learn)

# ==============================================================================

# A column of 1s must be added to the predictor matrix

# for the model intercept

X_train = sm.add_constant(X_train, prepend=True).rename(columns={'const':'intercept'})

model = sm.OLS(endog=y_train, exog=X_train)

model_res = model.fit()

print(model_res.summary())

OLS Regression Results

==============================================================================

Dep. Variable: y R-squared: 0.760

Model: OLS Adj. R-squared: 0.698

Method: Least Squares F-statistic: 12.28

Date: Sun, 11 Jan 2026 Prob (F-statistic): 1.02e-07

Time: 15:33:45 Log-Likelihood: -42.442

No. Observations: 40 AIC: 102.9

Df Residuals: 31 BIC: 118.1

Df Model: 8

Covariance Type: nonrobust

====================================================================================

coef std err t P>|t| [0.025 0.975]

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

intercept 70.3069 2.171 32.387 0.000 65.879 74.734

population 9e-05 4.15e-05 2.171 0.038 5.44e-06 0.000

ingresos 0.0002 0.000 0.663 0.512 -0.001 0.001

illiteracy 0.2330 0.487 0.479 0.635 -0.759 1.225

murder -0.3379 0.057 -5.925 0.000 -0.454 -0.222

college_graduate 0.0414 0.027 1.536 0.135 -0.014 0.096

frosts -0.0053 0.004 -1.241 0.224 -0.014 0.003

area -1.101e-06 2.2e-06 -0.501 0.620 -5.58e-06 3.38e-06

densidad_pobl -0.0012 0.001 -1.305 0.202 -0.003 0.001

==============================================================================

Omnibus: 3.407 Durbin-Watson: 2.538

Prob(Omnibus): 0.182 Jarque-Bera (JB): 1.741

Skew: -0.188 Prob(JB): 0.419

Kurtosis: 2.049 Cond. No. 2.07e+06

==============================================================================

Notes:

[1] Standard Errors assume that the covariance matrix of the errors is correctly specified.

[2] The condition number is large, 2.07e+06. This might indicate that there are

strong multicollinearity or other numerical problems.

The model with all variables introduced as predictors has a high $R^2$ (0.76), it is capable of explaining 76% of the variability observed in life expectancy. The model's p-value is significant (1.02e-07), so it can be considered that the model predicts the response variable better than would be expected by chance, at least one of the partial regression coefficients is different from 0. Many of the partial regression coefficients are not significant, which is an indicator that they might not contribute to the model, in the presence of the rest.

Selection of the Best Predictors¶

At the time of writing this document, statsmodels does not include any method for recursive predictor selection. Fortunately, it is relatively simple to achieve a basic implementation.

# Forward and backward selection functions for statsmodels linear models

# ==============================================================================

def forward_selection(

X: pd.DataFrame,

y: pd.Series,

criterion: str='aic',

add_constant: bool=True,

verbose: bool=True

)-> list:

"""

Performs a forward variable selection procedure using the specified

goodness metric as criterion. The procedure stops when it is no longer

possible to improve the model by adding variables.

Parameters

----------

X: pd.DataFrame

Predictor matrix

y: pd.Series

Response variable

criterion: str, default='aic'

Metric used to select variables. Must be one of the following

options: 'aic', 'bic', 'rsquared_adj'.

add_constant: bool, default=True

If `True` adds a column of 1s to the predictor matrix with the

name intercept.

verbose: bool, default=True

If `True` displays the results of each iteration on screen.

Returns

-------

selection: list

List with the selected variables.

"""

if add_constant:

X = sm.add_constant(X, prepend=True).rename(columns={'const':'intercept'})

remaining = X.columns.to_list()

selection = []

if criterion == 'rsquared_adj':

best_metric = -np.inf

last_metric = -np.inf

else:

best_metric = np.inf

last_metric = np.inf

while remaining:

metrics = []

for candidate in remaining:

temp_selection = selection + [candidate]

model = sm.OLS(endog=y, exog=X[temp_selection])

model_res = model.fit()

metric = getattr(model_res, criterion)

metrics.append(metric)

if criterion == 'rsquared_adj':

best_metric = max(metrics)

if best_metric > last_metric:

best_variable = remaining[np.argmax(metrics)]

else:

break

else:

best_metric = min(metrics)

if best_metric < last_metric:

best_variable = remaining[np.argmin(metrics)]

else:

break

selection.append(best_variable)

remaining.remove(best_variable)

last_metric = best_metric

if verbose:

print(f'variables: {selection} | {criterion}: {best_metric:.3f}')

return sorted(selection)

def backward_selection(

X: pd.DataFrame,

y: pd.Series,

criterion: str='aic',

add_constant: bool=True,

verbose: bool=True

)-> list:

"""

Performs a backward variable selection procedure using the specified

goodness metric as criterion. The procedure stops when it is no longer

possible to improve the model by removing variables.

Parameters

----------

X: pd.DataFrame

Predictor matrix

y: pd.Series

Response variable

criterion: str, default='aic'

Metric used to select variables. Must be one of the following

options: 'aic', 'bic', 'rsquared_adj'.

add_constant: bool, default=True

If `True` adds a column of 1s to the predictor matrix with the

name intercept.

verbose: bool, default=True

If `True` displays the results of each iteration on screen.

Returns

-------

selection: list

List with the selected variables.

"""

if add_constant:

X = sm.add_constant(X, prepend=True).rename(columns={'const':'intercept'})

# Start with all variables as predictors

selection = X.columns.to_list()

model = sm.OLS(endog=y, exog=X[selection])

model_res = model.fit()

last_metric = getattr(model_res, criterion)

best_metric = last_metric

if verbose:

print(f'variables: {selection} | {criterion}: {best_metric:.3f}')

while selection:

metrics = []

for candidate in selection:

temp_selection = selection.copy()

temp_selection.remove(candidate)

model = sm.OLS(endog=y, exog=X[temp_selection])

model_res = model.fit()

metric = getattr(model_res, criterion)

metrics.append(metric)

if criterion == 'rsquared_adj':

best_metric = max(metrics)

if best_metric > last_metric:

worst_variable = selection[np.argmax(metrics)]

else:

break

else:

best_metric = min(metrics)

if best_metric < last_metric:

worst_variable = selection[np.argmin(metrics)]

else:

break

selection.remove(worst_variable)

last_metric = best_metric

if verbose:

print(f'variables: {selection} | {criterion}: {best_metric:.3f}')

return sorted(selection)

# Forward variable selection

# ==============================================================================

predictors = forward_selection(

X = X_train,

y = y_train,

criterion = 'aic',

add_constant = False, # Already added previously

verbose = True

)

predictors

variables: ['intercept'] | aic: 143.990 variables: ['intercept', 'murder'] | aic: 104.951 variables: ['intercept', 'murder', 'college_graduate'] | aic: 102.243 variables: ['intercept', 'murder', 'college_graduate', 'population'] | aic: 99.607 variables: ['intercept', 'murder', 'college_graduate', 'population', 'frosts'] | aic: 97.043

['college_graduate', 'frosts', 'intercept', 'murder', 'population']

# Backward variable selection

# ==============================================================================

predictors= backward_selection(

X = X_train,

y = y_train,

criterion = 'aic',

add_constant = False, # Already added previously

verbose = True

)

predictors

variables: ['intercept', 'population', 'ingresos', 'illiteracy', 'murder', 'college_graduate', 'frosts', 'area', 'densidad_pobl'] | aic: 102.884 variables: ['intercept', 'population', 'ingresos', 'murder', 'college_graduate', 'frosts', 'area', 'densidad_pobl'] | aic: 101.179 variables: ['intercept', 'population', 'ingresos', 'murder', 'college_graduate', 'frosts', 'densidad_pobl'] | aic: 99.295 variables: ['intercept', 'population', 'murder', 'college_graduate', 'frosts', 'densidad_pobl'] | aic: 97.549 variables: ['intercept', 'population', 'murder', 'college_graduate', 'frosts'] | aic: 97.043

['college_graduate', 'frosts', 'intercept', 'murder', 'population']

Both strategies identify as the best model the one formed by the predictors: 'murder', 'population', 'frosts', 'college_graduate' along with the intercept.

# Train model with selected variables

# ==============================================================================

final_model = sm.OLS(endog=y_train, exog=X_train[predictors])

final_model_res = final_model.fit()

print(final_model_res.summary())

OLS Regression Results

==============================================================================

Dep. Variable: y R-squared: 0.747

Model: OLS Adj. R-squared: 0.718

Method: Least Squares F-statistic: 25.81

Date: Sun, 11 Jan 2026 Prob (F-statistic): 5.11e-10

Time: 15:33:45 Log-Likelihood: -43.521

No. Observations: 40 AIC: 97.04

Df Residuals: 35 BIC: 105.5

Df Model: 4

Covariance Type: nonrobust

====================================================================================

coef std err t P>|t| [0.025 0.975]

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

college_graduate 0.0475 0.017 2.772 0.009 0.013 0.082

frosts -0.0061 0.003 -2.057 0.047 -0.012 -7.93e-05

intercept 71.0177 1.079 65.845 0.000 68.828 73.207

murder -0.3101 0.042 -7.423 0.000 -0.395 -0.225

population 7.437e-05 3.5e-05 2.125 0.041 3.31e-06 0.000

==============================================================================

Omnibus: 3.043 Durbin-Watson: 2.502

Prob(Omnibus): 0.218 Jarque-Bera (JB): 1.525

Skew: -0.087 Prob(JB): 0.466

Kurtosis: 2.059 Cond. No. 4.66e+04

==============================================================================

Notes:

[1] Standard Errors assume that the covariance matrix of the errors is correctly specified.

[2] The condition number is large, 4.66e+04. This might indicate that there are

strong multicollinearity or other numerical problems.

Each slope in a multiple linear regression model (partial regression coefficients of the predictors) is defined as follows: If the other variables are held constant, for each unit increase in the predictor in question, the response variable $Y$ varies on average by as many units as indicated by the slope. For this example, for each unit increase in the college_graduate predictor, life expectancy increases on average by 0.0475 units, keeping the other predictors constant.

✏️ Note

How does this method differ from existing techniques in sklearn.feature_selection? Scikit-learn provides two main strategies for predictor selection:

- Use regression coefficients of each predictor, in the case of linear models, or other importance metric as in tree-based algorithms, to eliminate predictors.

- Use a user-defined validation metric (through fixed validation partition or cross-validation) to select the predictors that are removed or added.

# Predictor selection with sklearn SequentialFeatureSelector

# ==============================================================================

model = LinearRegression()

sfs = SequentialFeatureSelector(

model,

n_features_to_select = 'auto',

direction = 'forward',

scoring = 'r2',

cv = 5

)

sfs.fit(X_train, y_train)

sfs.get_feature_names_out().tolist()

['intercept', 'population', 'murder', 'densidad_pobl']

Following a sequential selection strategy based on $R^2$ and with 5-fold cross-validation, the selected predictors are: 'intercept', 'population', 'murder', 'population_density'.

✏️ Note

Normally, different methods do not obtain equivalent results. An effective approach is to identify the subset of predictors where the different methods agree. Although sequential/recursive variable selection has been widely used historically, new methods offer advantageous features. For example, the use of L1 penalty, also known as Lasso.

Residual Diagnostics¶

# Model residuals

# ==============================================================================

residuals = final_model_res.resid

# Training predictions

# ==============================================================================

train_prediction = final_model_res.predict(X_train[predictors])

Visual Inspection

# Plots

# ==============================================================================

fig, axes = plt.subplots(nrows=3, ncols=2, figsize=(7, 7))

axes[0, 0].scatter(y_train, train_prediction, edgecolors=(0, 0, 0), alpha = 0.4)

axes[0, 0].plot([y_train.min(), y_train.max()], [y_train.min(), y_train.max()], 'k--', lw=2)

axes[0, 0].set_title('Predicted vs actual value', fontsize=10)

axes[0, 0].set_xlabel('Actual')

axes[0, 0].set_ylabel('Prediction')

axes[0, 0].tick_params(labelsize = 7)

axes[0, 1].scatter(list(range(len(y_train))), residuals, edgecolors=(0, 0, 0), alpha=0.4)

axes[0, 1].axhline(y=0, linestyle='--', color='black', lw=2)

axes[0, 1].set_title('Model residuals', fontsize = 10)

axes[0, 1].set_xlabel('id')

axes[0, 1].set_ylabel('Residual')

axes[0, 1].tick_params(labelsize = 7)

sns.histplot(

data = residuals,

stat = "density",

kde = True,

line_kws = {'linewidth': 1},

alpha = 0.3,

ax = axes[1, 0]

)

axes[1, 0].set_title('Model residual distribution', fontsize=10)

axes[1, 0].set_xlabel("Residual")

axes[1, 0].tick_params(labelsize = 7)

sm.qqplot(

residuals,

fit = True,

line = 'q',

ax = axes[1, 1],

color = 'firebrick',

alpha = 0.4,

lw = 2

)

axes[1, 1].set_title('Model residuals Q-Q', fontsize=10)

axes[1, 1].tick_params(labelsize=7)

axes[2, 0].scatter(train_prediction, residuals, edgecolors=(0, 0, 0), alpha=0.4)

axes[2, 0].axhline(y=0, linestyle='--', color='black', lw=2)

axes[2, 0].set_title('Model residuals vs prediction', fontsize=10)

axes[2, 0].set_xlabel('Prediction')

axes[2, 0].set_ylabel('Residual')

axes[2, 0].tick_params(labelsize=7)

# Remove empty axes

fig.delaxes(axes[2,1])

fig.tight_layout()

plt.subplots_adjust(top=0.9)

fig.suptitle('Residual diagnostics', fontsize=12);

The residuals appear to be randomly distributed around zero, maintaining approximately the same variability along the X axis. This pattern suggests that normality and homoscedasticity of residuals are met.

Normality Test

It is checked whether the residuals follow a normal distribution using two statistical tests: Shapiro-Wilk test and D'Agostino's K-squared test. The latter is the one included in the statsmodels summary under the name Omnibus.

In both tests, the null hypothesis considers that the data follow a normal distribution, therefore, if the p-value is not lower than the selected alpha reference level, there is no evidence to discard that the data are normally distributed.

# Shapiro-Wilk test for normality of residuals

# ==============================================================================

shapiro_test = stats.shapiro(residuals)

print(f"Shapiro-Wilk test: statistic = {shapiro_test[0]}, p-value = {shapiro_test[1]}")

# D'Agostino's K-squared test for normality of residuals

# ==============================================================================

k2, p_value = stats.normaltest(residuals)

print(f"D'Agostino's K-squared test: statistic = {k2}, p-value = {p_value}")

Shapiro-Wilk test: statistic = 0.9700626181524045, p-value = 0.3615595274062995 D'Agostino's K-squared test: statistic = 3.0425718093772716, p-value = 0.21843082505945458

Both graphical analysis and hypothesis tests confirm normality.

Homoscedasticity

When plotting the residuals against the values fitted by the model ("Model residuals vs prediction" plot), the former are distributed randomly around zero, maintaining approximately the same variability along the X axis.

# Breusch-Pagan test

# ==============================================================================

lm, lm_p_value, fvalue, f_p_value = het_breuschpagan(residuals, X_train[predictors])

print(f"Statistic= {fvalue}, p-value = {f_p_value}")

Statistic= 2.382568392873267, p-value = 0.07014338688022724

Neither the graphical analysis nor the hypothesis test show signs of lack of homoscedasticity.

Multicollinearity (Variance Inflation VIF)

# Correlation between numerical predictors

# ==============================================================================

corr_matrix = X_train[predictors].corr(method='pearson')

tril = np.tril(np.ones(corr_matrix.shape)).astype(bool)

corr_matrix[tril] = np.nan

corr_matrix_tidy = corr_matrix.stack().reset_index(name='r')

corr_matrix_tidy = corr_matrix_tidy.rename(columns={'level_0': 'variable_1', 'level_1': 'variable_2'})

corr_matrix_tidy = corr_matrix_tidy.dropna()

corr_matrix_tidy['r_abs'] = corr_matrix_tidy['r'].abs()

corr_matrix_tidy = corr_matrix_tidy.sort_values('r_abs', ascending=False).reset_index(drop=True)

corr_matrix_tidy

| variable_1 | variable_2 | r | r_abs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | frosts | murder | -0.549982 | 0.549982 |

| 1 | college_graduate | murder | -0.517231 | 0.517231 |

| 2 | college_graduate | frosts | 0.448608 | 0.448608 |

| 3 | murder | population | 0.366638 | 0.366638 |

| 4 | frosts | population | -0.228660 | 0.228660 |

| 5 | college_graduate | population | -0.195857 | 0.195857 |

# VIF calculation

# ==============================================================================

vif = pd.DataFrame()

vif["variables"] = X_train[predictors].columns

vif["VIF"] = [variance_inflation_factor(X_train[predictors].values, i) for i in range(X_train[predictors].shape[1])]

vif

| variables | VIF | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | college_graduate | 1.441241 |

| 1 | frosts | 1.515200 |

| 2 | intercept | 78.917401 |

| 3 | murder | 1.788412 |

| 4 | population | 1.156697 |

According to statsmodels documentation, if VIF is greater than 5, then the predictor is highly collinear with the other predictors.

There are no predictors that show very high linear correlation or variance inflation.

Predictions¶

Once the model has been trained, predictions can be obtained for new data.

# Test set predictions

# ==============================================================================

X_test = sm.add_constant(X_test, prepend=True).rename(columns={'const':'intercept'})

final_model_res.predict(X_test[predictors])

37 71.627080 45 70.197194 6 72.102241 44 71.038126 13 70.982884 36 72.470001 8 70.749750 29 71.745882 4 72.255344 49 70.842206 dtype: float64

# Predictions with confidence interval

# ==============================================================================

# The mean column contains the mean of the prediction

predictions = final_model_res.get_prediction(exog = X_test[predictors]).summary_frame(alpha=0.05)

predictions

| mean | mean_se | mean_ci_lower | mean_ci_upper | obs_ci_lower | obs_ci_upper | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 37 | 71.627080 | 0.340585 | 70.935656 | 72.318503 | 69.921765 | 73.332394 |

| 45 | 70.197194 | 0.144249 | 69.904353 | 70.490036 | 68.611071 | 71.783317 |

| 6 | 72.102241 | 0.188786 | 71.718985 | 72.485497 | 70.496964 | 73.707519 |

| 44 | 71.038126 | 0.211805 | 70.608140 | 71.468113 | 69.421055 | 72.655197 |

| 13 | 70.982884 | 0.143523 | 70.691516 | 71.274252 | 69.397032 | 72.568735 |

| 36 | 72.470001 | 0.317495 | 71.825451 | 73.114551 | 70.783148 | 74.156854 |

| 8 | 70.749750 | 0.305186 | 70.130190 | 71.369310 | 69.072286 | 72.427213 |

| 29 | 71.745882 | 0.214940 | 71.309531 | 72.182233 | 70.127107 | 73.364657 |

| 4 | 72.255344 | 0.677814 | 70.879309 | 73.631379 | 70.176041 | 74.334647 |

| 49 | 70.842206 | 0.271753 | 70.290518 | 71.393894 | 69.188607 | 72.495805 |

Test Error¶

# Model test error

# ==============================================================================

error = rmse(y_test.flatten(), predictions['mean'])

print(f"The test error (rmse) is: {error}")

The test error (rmse) is: 0.5791307323513487

Interpretation¶

The multiple linear regression model

$$Life \ Expectancy =$$$$71.0177 + 7.437^{-05} population - 0.3101 murder + 0.0475 college\_graduate -0.0061 frosts$$is capable of explaining 74.7% of the variability observed in life expectancy (R2: 0.747, R2-Adjusted: 0.718). The F test shows that it is significant (p-value: 5.11e-10). All conditions for this type of multiple regression are satisfied.

Session Information¶

import session_info

session_info.show(html=False)

----- matplotlib 3.10.8 numpy 2.2.6 pandas 2.3.3 scipy 1.15.3 seaborn 0.13.2 session_info v1.0.1 sklearn 1.7.2 statsmodels 0.14.6 ----- IPython 9.8.0 jupyter_client 8.7.0 jupyter_core 5.9.1 ----- Python 3.13.11 | packaged by Anaconda, Inc. | (main, Dec 10 2025, 21:28:48) [GCC 14.3.0] Linux-6.14.0-37-generic-x86_64-with-glibc2.39 ----- Session information updated at 2026-01-11 15:33

Bibliography¶

Linear Models with R by Julian J.Faraway

OpenIntro Statistics: Fourth Edition by David Diez, Mine Çetinkaya-Rundel, Christopher Barr

Introduction to Machine Learning with Python: A Guide for Data Scientists

Krzywinski, M., Altman, N. Multiple linear regression. Nat Methods 12, 1103–1104 (2015)

Citation Instructions¶

How to cite this document?

If you use this document or any part of it, we appreciate that you cite it. Thank you very much!

Multiple Linear Regression with Python by Joaquín Amat Rodrigo, available under an Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 DEED) license at https://cienciadedatos.net/documentos/py10b-regresion-lineal-multiple-python.html

Did you like the article? Your help is important

Your contribution will help me continue generating free educational content. Thank you very much! 😊

This document created by Joaquín Amat Rodrigo is licensed under Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International.

Permitted:

-

Share: copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format.

-

Adapt: remix, transform and build upon the material.

Under the following terms:

-

Attribution: You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.

-

NonCommercial: You may not use the material for commercial purposes.

-

ShareAlike: If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you must distribute your contributions under the same license as the original.